The Arabian horse breed is one of the most easily recognized horse breeds in the world. Also called an Arab, it originated somewhere on the Arabian Peninsula, but the exact location is unknown.

The Arabian Peninsula in southwest Asia includes the present day countries of Saudi Arabia, Yemen Arab Republic, People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Kuwait. These countries were divided in ancient times into Arabia Deserta, Arabia Petraea, and Arabia Felix.

Arabian horses are known for speed, refinement, endurance, and strong bones.

Origin: The origin of the Arabian horse remains a great zoological mystery. Although this unique breed has had a distinctive national identity for centuries, its history nevertheless is full of subtleties, complexities and contradictions. It defies simple interpretation.

When we first encounter the Arabian, or the prototype of what is known today as the Arabian, he is somewhat smaller than his counterpart today. Otherwise he has essentially remained unchanged throughout the centuries.

Authorities are at odds about where the Arabian horse originated. The subject is hazardous, for archaeologists’ spades and shifting sands of time are constantly unsettling previously established thinking. There are certain arguments for the ancestral Arabian having been a wild horse in northern Syria, southern Turkey and possibly the piedmont regions to the east as well.

The area along the northern edge of the Fertile Crescent comprising part of Iraq and running along the Euphrates and west across Sinai and along the coast to Egypt, offered a mild climate and enough rain to provide an ideal environment for horses.

Other historians suggest this unique breed originated in the southwestern part of Arabia, offering supporting evidence that the three great river beds in this area provided natural wild pastures and were the centers in which Arabian horses appeared as undomesticated creatures to the early inhabitants of southwestern Arabia.

Because the interior of the Arabian peninsula has been dry for approximately 10,000 years, it would have been difficult, if not impossible, for horses to exist in that arid land without the aid of man. The domestication of the camel in about 3500 B.C. provided the Bedouins (nomadic inhabitants of the middle east desert regions) with means of transport and sustenance needed to survive the perils of life in central Arabia, an area into which they ventured about 2500 B.C. At that time they took with them the prototype of the modern Arabian horse.

There can be little dispute, however, that the Arabian horse has proved to be, throughout recorded history, an original breed-which remains to this very day.

Neither sacred nor profane history tells us the country where the horse was first domesticated, or whether he was first used for work or riding. He probably was used for both purposes in very early times and in various parts of the world. We know that by 1500 B.C. the people of the east had obtained great mastery over their hot-blooded horses which were the forerunners of the breed which eventually became known as “Arabian.”

About 3500 years ago the hot-blooded horse assumed the role of king-maker in the east, including the valley of the Nile and beyond, changing human history and the face of the world. Through him the Egyptians were made aware of the vast world beyond their own borders. The Pharaohs were able to extend the Egyptian empire by harnessing the horse to their chariots and relying on his power and courage.

With his help, societies of such distant lands as the Indus Valley civilizations were united with Mesopotamian cultures. The empires of the Hurrians, Hittites, Kassites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians and others rose and fell under his thundering hooves. His strength made possible the initial concepts of a cooperative universal society, such as the Roman empire.

This awe-inspiring horse of the east appears on seal rings, stone pillars and various monuments with regularity after the 16th century B.C. Egyptian hieroglyphics proclaim his value; Old Testament writings are filled with references to his might and strength.

Other writings talk of the creation of the Arabian, “thou shallst fly without wings and conquer without swords.” King Solomon some 900 years B.C. eulogized the beauty of “a company of horses in Pharaoh’s chariots,” while in 490 B.C. the famous Greek horseman, Xinophon proclaimed: “A noble animal which exhibits itself in all its beauty is something so lovely and wonderful that it fascinates young and old alike.”

But whence came the “Arabian horse?” We have seen this same horse for many centuries before the word “Arab” was ever used or implied as a race of people or species of horse.

The origin of the word “Arab” is still obscure. A popular concept links the word with nomadism, connecting it with the Hebrew “Arabha,” dark land or steppe land, also with the Hebrew “Erebh,” mixed and hence organized as opposed to organized and ordered life of the sedentary communities, or with the root “Abhar”-to move or pass.

“Arab” is a Semitic word meaning “desert” or the inhabitant thereof, with no reference to nationality. In the Koran a’rab is used for Bedouins (nomadic desert dwellers) and the first certain instance of its Biblical use as a proper name occurs in Jer. 25:24: “Kings of Arabia,” Jeremiah having lived between 626 and 586 B.C.

The Arabs themselves seem to have used the word at an early date to distinguish the Bedouin from the Arabic-speaking town dwellers.

This hot blooded horse which had flourished under the Semitic people of the east now reached its zenith of fame as the horse of the “Arabas.” The Bedouin horse breeders were fanatic about keeping the blood of their desert steeds absolutely pure, and through line-breeding and inbreeding, celebrated strains evolved which were particularly prized for distinguishing characteristics and qualities.

The mare evolved as the Bedouin’s most treasured possession. The harsh desert environment ensured that only the strongest and keenest horse survived, and it was responsible for many of the physical characteristics distinguishing the breed to this day.

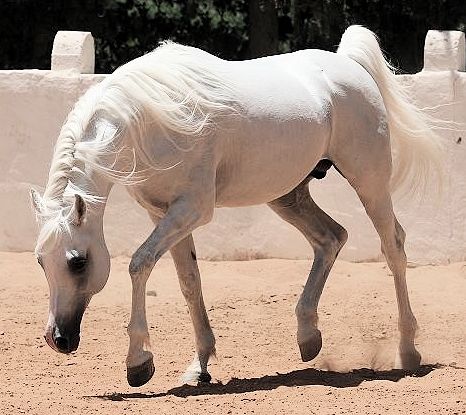

Colors: Chestnut, grey, roan, bay and black.

Height: between 14.2 and 15hh.

Conformation: small, elegant concave head, curved neck, long sloping shoulder, broad chest and deep body, short back, hard clean limbs, hard well-shaped feet, fine mane and tail.

Character: Intelligent, responsive. Their desert origins mean they are well adapted to harsh conditions – endurance, soundness and the ability to thrive on meager rations.

Uses: riding, showing, endurance racing.

History: Arabian bloodlines are found in the foundation stock of almost every modern breed of riding horse. Selective breeding for traits including an ability to form a cooperative relationship with humans created a horse breed that is good-natured, quick to learn, and willing to please. The Arabian also developed the high spirit and alertness needed in a horse used for raiding and war.

They are one of the top ten most popular horse breeds in the world, and one of the most beautiful horse breeds. They are especially noted for their endurance, and the superiority of the breed in Endurance riding competitions demonstrates that well-bred Arabians are strong, sound horses with superior stamina.

Arabian Conformation

Arabian horses have refined, wedge-shaped heads, a broad forehead, large eyes, large nostrils, and small muzzles. Most display a distinctive concave, or “dished” profile.

Many Arabians also have a slight forehead bulge between their eyes, called the jibbah by the Bedouin, that adds additional sinus capacity, believed to have helped the Arabian horse in its native dry desert climate.

Another breed characteristic is an arched neck with a large, well-set windpipe set on a refined, clean throatlatch. Other distinctive features are a relatively long, level croup, or top of the hindquarters, and naturally high tail carriage.

Well-bred Arabians have a deep, well-angled hip and well laid-back shoulder. Within the breed, there are variations. Some individuals have wider, more powerfully muscled hindquarters suitable for intense bursts of activity in events such as reining, while others have longer, leaner muscling better suited for long stretches of flat work such as endurance riding or horse racing.

Most have a compact body with a short back.Arabians usually have dense, strong bones, and good hoof walls.

Skeletal analysis

Some Arabians, though not all, have 5 lumbar vertebrae instead of the usual 6, and 17 pairs of ribs rather than 18. A quality Arabian has both a relatively horizontal croup and a properly angled pelvis as well as good croup length and depth to the hip (determined by the length of the pelvis), that allows agility and impulsion.

A misconception confuses the topline of the croup with the angle of the “hip” (the pelvis or ilium), leading some to assert that Arabians have a flat pelvis angle and cannot use their hindquarters properly. However, the croup is formed by the sacral vertebrae.

The hip angle is determined by the attachment of the ilium to the spine, the structure and length of the femur, and other aspects of hindquarter anatomy, which is not correlated to the topline of the sacrum.

The hip angle is determined by the attachment of the ilium to the spine, the structure and length of the femur, and other aspects of hindquarter anatomy, which is not correlated to the topline of the sacrum.

So, the Arabian has conformation typical of other horse breeds built for speed and distance, such as the Thoroughbred, where the angle of the ilium is more oblique than that of the croup. Thus, the hip angle is not necessarily correlated to the topline of the croup.

Horses bred to gallop need a good length of croup and good length of hip for proper attachment of muscles, and so unlike angle, length of hip and croup do go together as a rule.

Arabian Colors

The Arabian Horse Association registers purebred horses with the coat colors bay, gray, chestnut, black, and roan. Bay, gray and chestnut are the most common; black is less common. The classic roan gene does not appear to exist in Arabians. Arabians registered by breeders as “roan” are usually expressing rabicano or, sometimes, sabino patterns with roan features.

Purebred Arabians never carry dilution genes. Therefore, purebreds cannot be colors such as dun, cremello, palomino or buckskin. However, there is pictorial evidence from Ancient Egypt suggesting that spotting patterns may have existed on ancestral Arabian-type horses in antiquity.

Purebred Arabians today do not carry genes for pinto or Leopard complex (“Appaloosa”) spotting patterns, except for sabino.

One spotting pattern, sabino, does exist in purebred Arabians. Sabino coloring is characterized by white markings such as “high white” above the knees and hocks, irregular spotting on the legs, belly and face, white markings that extend beyond the eyes or under the chin and jaw, and sometimes lacy or roaned edges.

Although many Arabians appear to have a “white” hair coat, they are not genetically “white”. This color is usually created by the natural action of the gray gene, and virtually all white-looking Arabians are actually grays.

Grey Arabian Stallion |

| Buy This Arabian Horse Portrait |

There are a very few Arabians registered as “white” having a white coat, pink skin and dark eyes from birth. These animals are believed to manifest a new form of dominant white, a result of a nonsense mutation in DNA tracing to a single stallion foaled in 1996.

This horse was originally thought to be a sabino, but actually was found to have a new form of dominant white mutation, now labeled W3. It is possible that white mutations have occurred in Arabians in the past or that mutations other than W3 exist but have not been verified by genetic testing.

To produce horses with some Arabian characteristics but coat colors not found in purebreds, they have to be crossbred with other breeds. Though the purebred Arabian produces a limited range of potential colors, they do not appear to carry any color-based lethal disorders such as the frame overo gene (“O”) that can produce lethal white syndrome (LWS).

All Arabians, no matter their coat color, have black skin, except under white markings. Black skin provided protection from the intense desert sun.